Chum Bycatch Means More Closures for Pollock Fleet

Tuesday, July 12 2011

The pollock fleet is allowing more fishing grounds in the Bering Sea to be closed in an effort to reduce the high levels of chum bycatch.

On Monday, representatives from the pollock cooperatives agreed to expand the salmon bycatch avoidance zone by another 1,000 square nautical miles. That brings the total area that can be closed at any given time to 5,000 square miles.

So far, the fleet has taken an unusually high number of chums this B season. As of this week, it had taken approximately 53,000 chum salmon. Last year, only 13,000 chums were taken over the course of the whole season. Most of that bycatch was taken during the first two weeks of the season, before the fleet started making targeted closures based on where salmon was being caught – a system known as the rolling hotspot program.

“If there were no rolling hotspot program, we would be in the hundreds of thousands of chum salmon by now,” says John Gruver, the inter-coop manager with United Catcher Boats. That would really be well ahead of any pace we’d been on before.”

Because chum and pollock often go after the same food sources, they usually mingle in the same waters, which is bad for fishermen.

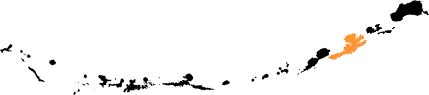

“The most productive area with the most valuable pollock happen to be right beside these rolling hotspot closures that are just north of Unimak Pass,” says Gruver. “So, what we’re doing is shutting everybody out of the best pollock ground and moving them off into other areas where there is some bycatch still, but much slower pollock fishing."

That means that boats have to travel farther out, and spend more money on fuel.

“Anytime you make a boat move or run further, their costs are going to go up,” Gruver adds.

But still, the big priority for the fleet right now is bringing down bycatch numbers and helping ensure that runs in western Alaska are strong.

Joe Garnie lives out in western Alaska in the village of Teller. He testified on the chum bycatch issue at the North Pacific Fishery Management Council’s June meeting in Nome. He worries that high levels of chum bycatch mean that the salmon doesn’t make it up to him and other subsistence users. While he used to be able to catch over 100 chum salmon a day during the summer months, now he’s only bringing in about 60 on average.

“We’re an impoverished community. You take our kings –- they’re extinct. You take our reds – they’re diminished down to near nothing,” says Garnie. “The only thing we’ve got left are chums. It’s painting a very grim picture.”

But Gruver says that when chum bycatch is plentiful and hard to avoid, that usually means strong runs later in the season. So far this year, salmon runs in the Norton Sound and Yukon-Kuskokwim regions have been at pace, and 3 million chums have been harvested statewide.

And more importantly, he adds, it’s not clear that the bycatch the pollock fleet is taking is necessarily heading toward western Alaska.

“A lot of the fish are not western Alaska fish at all,” says Gruver. “They’re Asian and Russian hatchery fish.”

He says that down the road, genetic analysis of these fish could help reduce bycatch of Western Alaska chums, especially if that approach is used in conjunction with the rolling hotspot program and gear like salmon excluder devices.

But in the meantime, the pollock fleet is hoping that cautious fishing will be enough.