DNA Clarifies Steller Sea Lion Diet

Thursday, December 01 2011

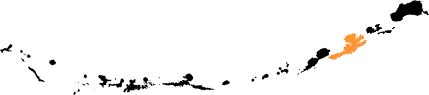

How to manage Steller sea lions is a controversial topic. The State of Alaska recently sued the National Marine Fisheries Service over its decision to close fisheries in parts of the Aleutian chain in order to protect the endangered western stock. That case will be heard in court on December 21.

NFMS says the population out west is declining because the sea lions have to compete with commercial fisheries for food. The State says there isn’t enough data to back that theory up.

While the government dukes it out in court, one scientist is trying to figure out better ways to analyze sea lion diets.

It’s difficult to gather precise data about sea lion foraging, since they search for food underwater and out of sight.

But Ella Bowles, while doing her Master's degree at the University of British Columbia, may have found a way to make studying them easier. Her equation is common sense: figure out what goes in by analyzing what comes out. This has been standard practice in assessing marine mammal diets for years. But until now, the measuring technique has been based on identifying ‘hard parts’ - like bone - in the animal’s feces. According to Bowles, that’s pretty imprecise.

“There are lots of different biases that are introduced by looking at different types of bone structures because they are digested in different ways.”

Bowles’ study uses DNA to identify the different quantities of marine species in sea lion scat. She says her results are accurate to within 12 percent. What that means is that if the DNA results show sea lions eating 60 percent mackerel, Bowles can say with confidence that their diet consists of between 48 and 72 percent mackerel.

That may be more precise than previous methods, but it’s still a wide range. Bowles says that can be a problem if the animals have a varied diet.

“That 12 percent means more if we’re looking at a prey that is only a very small percentage of their diet, if that prey is very important.”

Despite that, DNA does allow scientists to get much more precise measurements of cephalopods like squid, which are potentially a large part of the sea lion diet, but are difficult to measure with the hard parts method.

All of Bowles’ research was done in a laboratory, with caged sea lions, but she hopes her methods can be applied in the wild. She says collecting sea lion scat is actually easier than it might seem.

“They behave like oversized dogs, so basically you just drive up to a haul-out in your boat.”

But even with scat samples, there are challenges to turning the data into management information. No one has figured out how to go backwards from the proportions to how much food was actually consumed.

Bowles says that makes it difficult to know how much of a particular species is needed to maintain healthy sea lion populations.

“If we can get the kilogram amount that that percentage of the sea lion’s diet represents, then we can know how much of that resource needs to be maintained.”

Even knowing what and how much sea lions eat though doesn’t necessary translate into knowing what makes them healthy. But it’s a start.