Management Biologists Recommend Keeping Pollock Cap at Same Level

Thursday, November 17 2011

Next year’s pollock numbers might not change much after all.

Management biologists met yesterday in Seattle to come up with a recommendation for next year’s harvest levels. A draft assessment had suggested that allowable biological catch -- the upper threshold for the harvest level -- should be put at 1.08 million metric tons, a 14 percent drop over this year’s quota. The assessment noted that the results of the pollock survey were lower than expected, catch rates by fishermen were low this fall, and there’s still uncertainty about the amount of young pollock in the Bering Sea.

Instead of going with that number, the groundfish plan team is instead recommending that the allowable biological catch be put at 1.22 million metric tons. That’s close to the amount of pollock that vessels were allowed to take this year.

Jim Ianelli is a biologist with the National Marine Fisheries Service, and he was the lead author of the stock assessment that was used as a starting point for discussion. He says that the plan team went with the higher number because they wanted to stick with the modeling approach they used last year, unless there was a clear reason not to.

He adds that it was a matter of consistency.

“If they always ignored information, they would have to ignore it for a lot of the stocks,” says Ianelli.

The sticking point during the discussion was figuring out how many pollock were born in 2008, and how many survived. According to NMFS estimates, that year class of pollock is one of the more abundant groups in the water right now. But because scientists can never get an exact figure of the amount of pollock in the ocean at any given time and because that group of pollock wasn’t behaving as expected, the stock assessment authors suggested that the groundfish plan team treat that bunch like an average group when running their numbers.

That didn’t seem appropriate to NMFS biologist Grant Thompson, who argued during the meeting that the management of the fishery is already cautious and that taking a different approach to managing the fishery this year would be poor precedent.

“I am unsettled by the fact that this model -- and rightly so -- is our gold standard, and it’s the only place where we’re thinking of cutting our [allowable biological catch] in half because we’re uncertain about things,” said Thompson.

As far as why this year didn’t meet expectations, there isn’t a conclusive explanation yet. The quota had been set at about 1.25 million metric tons, but fishermen left about 5 percent of that in the water. It’s been 20 years since that much fish was left on the table.

Ianelli says that one of the big challenges to managing the fishery is that even management biologists are confident in their annual assessment of how much pollock is in the water, they can’t predict where they’ll be or how they’ll behave.

“There’s more data collected on Bering Sea pollock than almost any other species anywhere, but even with that precision of knowing how much is being caught and estimating with our surveys how many are out there, that the pollock will behave differently in different years,” says Ianelli. “It’s kind of like predicting the weather -- you know, you can’t tell what will happen too far out.”

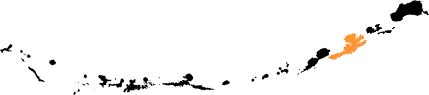

The final quota will not be set until December, when the North Pacific Fishery Management Council meets in Anchorage. The Bering Sea pollock fishery is Alaska’s largest, and much of that product is processed locally in Unalaska.