New Book Casts Spotlight on Traditional Foods

Thursday, August 21 2014

Food has been a crucial part of the Unangan culture for centuries. But in the Aleutian and Pribilof islands, people are relying less on the land and sea and more on their local store.

KUCB’s Lauren Rosenthal reports on a new effort to promote subsistence living -- in print.

From sweet Russian tea to fermented fur seal flipper, the traditional diet in the Aleutians and Pribilofs has always been pretty varied.

But a decade ago, Suanne Unger realized it might be starting to fade. She was in the villages of St. Paul and Atka, to interview people about their eating habits.

Unger: "There were comments like, ‘My grandmother passed away and she used to be the one that cooked traditional foods with us.’ Or ‘I don’t know how to prepare traditional foods. We were getting all sorts of feedback that indicated that some loss of traditional food production knowledge was taking place."

That raised a red flag with Unger. She’s a researcher for the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, and she says traditional foods cut the risk of diabetes. Plus gathering them is good exercise.

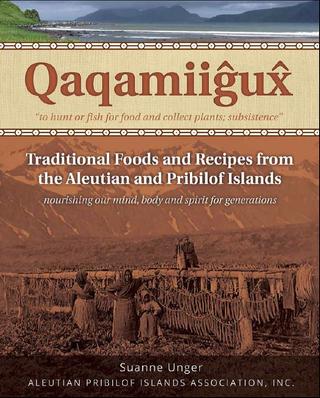

So Unger applied for a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – and used the money to make a recipe book for the Aleutian and Pribilof islands.

Unger: "That is the easiest way to describe [it], because it has recipes, and I’m at fault for even sometimes calling it that. But really, it is a lot more than a cookbook."

It’s called "Qaqamiiĝux̂." That’s the Aleut word for subsistence, and it covers a lot more ground than just cooking.

Unger wove in dozens of interviews with elders about their best practices for hunting, their safety tips -- and even detailed nutritional facts.

Unger: "Like the iron, for example that’s found in Steller sea lion meat or, you know, the protein found in reindeer."

That way, readers can make comparisons to the store-bought products they’ve come to rely on. But Unger says those are probably here to stay.

Whether it’s commercial fishing or construction, a lot of residents in the region are part of the cash economy now. And they don’t have time for subsistence.

Julia Dushkin has seen that change firsthand in Unalaska.

Dushkin: "Well, it’s hard nowadays to go out hunting and everything. Like, sea lion for instance? That’s hard to get. And I love sea lion meat, versus seal and that other stuff."

Dushkin is standing in the middle of Unalaska’s annual culture camp. For one week, elders stop their daily routines and teach traditional skills.

Larry Dirks: "Don’t cut the skin, eh?"

Larry Dirks is showing a 10-year-old how to fillet her first salmon. Olivia Betzen glides her knife through the meat -- until it slips out of her slimy hands.

Olivia: "Oops. Better use this one."

Olivia reaches for a blade with a bumpy handle. And she makes the last few cuts:

Dirks: "Yep, that should do it?"

Olivia: "Got it."

Dirks: "Yep! We’re all done, eh?"

As Olivia carries her salmon up the beach, Larry Dirks starts washing his knives. He works for Unalaska’s Department of Public Safety now, but he learned how to fish and hunt back home in Atka.

Dirks: "Filleting fish and all that takes years. Took me years to get good at it. But it’s a start, anyways, for these kids."

It’s the kids that Suanne Unger wants to target next. Eventually, she hopes her subsistence book will make its way into the classroom.

Unger: "You know, my dream would be to take this and create some curriculum out of it and have it for teachers to pick up throughout our region. I don’t know if we’ll be able to manage to get something going soon. But that would be the direction I’d like to see this take."

Along with hands-on learning, it could help create a new generation of hungry students.

To learn more about traditional foods -- or to purchase a copy of "Qaqamiiĝux̂" for $25 -- you can visit the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association website.