North Slope and Northwest Arctic Borough representatives examine Shell oil spill response fleet

Friday, December 10 2010

Unalaska, AK – On Thursday, a group of two dozen community leaders from the Northwest Arctic and North Slope Boroughs traveled out to Unalaska to examine Shell's oil spill response fleet. The federal government has agreed to process Shell's application to drill an exploratory well in the Beaufort Sea next summer, and now the company is addressing environmental and social concerns held by local officials and tribal representatives.

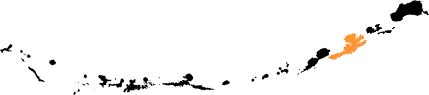

The trip south to Unalaska has been a big part of that. In early November, Shell first approached the group with offers to inspect the oil response vessel Nanuq and the mobile drill rig Kulluk, which are being moored in Captains Bay through the winter. At a distance of 1300 miles, Dutch Harbor is the closest deepwater port to the proposed well site.

After weeks of planning, the most of the group arrived on Thursday morning on a charter flight. They were addressed by Shell vice president Pete Slaiby, who oversees Shell's Alaska operations, and they heard presentations about spill response plans from representatives from Alaska Cleans Seas amd Arctic Slope Energy Services.

The most important part of the day, though, involved getting out on the Nanuq and getting close to the Kulluk. The Nanuq is an ice-class cleanup vessel, and on its deck were many of Shell's spill response tools.

While onboard the vessel, the questions were mostly technical. The group asked how the tools worked and what sort of back-up plans existed in case the equipment failed. But during the question and answer session later that night, the focus was more on the social impact Shell's operations would have. The effect on subsistence harvest was an important topic, as was job creation and support of local schools. Kotzebue mayor Siikauraq Whiting says that while opinion is split on off-shore drilling in her community, it's important that area leaders work to be included in the resource development process and have their voices heard, since ultimately it's the federal government deciding the status of the drilling leases.

"Our people are going to be here forever, and we need to make sure that our people and our way of life is not threatened so we can continue to live off the marine mammals and continue to live off the land," she says.

Whiting says that while Shell has done a good job of communicating with local governments and Native groups, she's still worried about what a spill would mean for her region. She says that there are often white-out storms in her area that would make it hard to respond to an emergency. She also has reservations about dumping dispersants or burning oil during a spill response, as they could harm marine life.

"You can't mess with Mother Nature," says Whiting. "The surface of the ice is just the surface. There's a ton more on the bottom. It looks like just a little ice cubes in a glass of water, but these are big, huge, monumental chunks of ice, and as high tech as we are, I still need to be confident that they would be able to safely clean our waters."

Still, many of the members of the group were impressed by Shell's response capacity. And many appreciated the chance to get out to Unalaska and see parts of the response fleet.

"Every meeting we had, our concerns were: Are they safe? Are they going to do the job? Do they have enough equipment on each vessel?" says John Goodwin, who represented the tribally-operated non-profit Maniilaq.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement is still working on an environmental impact statement for the region.