Scientists, Fishermen Struggle to Organize Research Efforts

Friday, November 22 2013

In Alaska, fishermen and scientists have a long history of working together to study the best way to catch seafood. And now that federal budgets are on the decline, they’re interested in doing more.

But as KUCB’s Lauren Rosenthal reports, researchers and trade groups around the state are struggling to line up their efforts.

Craig Rose works for the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. And for the past decade, a lot of his effort has gone into the Bering Sea pollock fleet.

Rose works on gear modifications to cut down on bycatch and habitat disruptions. One of his big projects has been salmon excluders, which keep pollock in a trawl net and skip over Chinook and chum salmon.

For work like that, Rose says:

Rose: "You need to bring the people that know the gear and know the fish in early, so you can work with something that is actually going to apply to the fishery."

The pollock fleet helped Rose test drive excluder nets in tanks and out at sea, over and over, until they found one that worked.

It’s a prime example of a practice called cooperative research:

Rose: "Fisheries agencies and the fishing industry work together to solve problems, to collect information."

In theory, it’s an ideal partnership. But Rose says some of these research projects are running into roadblocks:

Rose: "There is a shortage of funding and it’s scattered. In terms of the ability to coordinate and bring things together? That structure is not there."

Right now, industry trade groups are funneling money into research boards. There are more than a dozen of them out there, just operating in the North Pacific and Bering Sea.

It’s up to those boards to find scientists who want to work with the commercial fishing fleet on a research project. And it’s up to the boards to help the commercial vessels get the right government permits to allow them to participate.

John Gauvin has set up plenty of these research partnerships. He says it can take a few years to get the projects off the ground, and once they start, the research teams can get laser-focused on their subject -- like incidental catch in the pollock fishery.

Gauvin: "We might want to think about what you’d learn about fish behavior between pollock and those species at the same time. But you’re out there, going, ‘Oh, well, we’re working on salmon bycatch.’"

Gauvin says it doesn't have to be like that anymore.

Gauvin: "There’s ways to get more out of your research dollar if you can have a planning process and a systematic approach."

In a presentation at the Pacific Marine Expo in Seattle last week, Gauvin made a case for getting the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration involved.

NOAA’s used congressional line-item money to set up regional offices for overseeing this kind of research. There’s one in the southeast and one in the northeast United States.

In his presentation, Gauvin said Alaska needs one, too. But Gauvin says he’s really open to anything that would get research better organized:

Gauvin: "It’s not necessarily a government program. It might be some amalgam of industry and government and universities. But it would be something that brings the parties together in a way that we haven’t been able to do in these sort of ad hoc individual efforts."

Jim Ruhle is an East Coast fisherman, born and bred. He says Alaska shouldn’t back off the idea of getting the government involved so easily.

With NOAA’s regional boards in place, Ruhle says East Coast fishery management councils were able to set up a reliable source of funding for cooperative research.

The source? Seafood itself.

Ruhle: "In other words, the management council has the ability to set aside a portion of that -- up to 3 percent -- of the stock. And that stock is converted to dollars through an auction process where the fish are sold back to the fishery."

Ruhle says it’s not a perfect system. But since 2008, it’s paid for him to fish with scientists aboard his 90-foot trawler, the F/V Darana R.

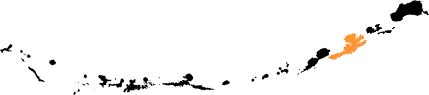

Ruhle and the crew do two trawls a year from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, gathering data for multiple fisheries stock assessments. Now that they have finally have enough data, their finds are finally making their way to fisheries managers.

Ruhle says he’s hoping more fishermen will follow his example – on the East Coast, and in Alaska.

Ruhle: "It’s foolish not to be involved. When you’re on the ocean and fishing, you experience change and adapt to change. By being involved with cooperative research, now you adapt to change and improve it scientifically, to where, other people can benefit."

It’s just a matter of making sure those people know how to get started.