Shell’s Icebreaker Heads North For Oil; The Coast Guard’s, For Science

Friday, August 07 2015

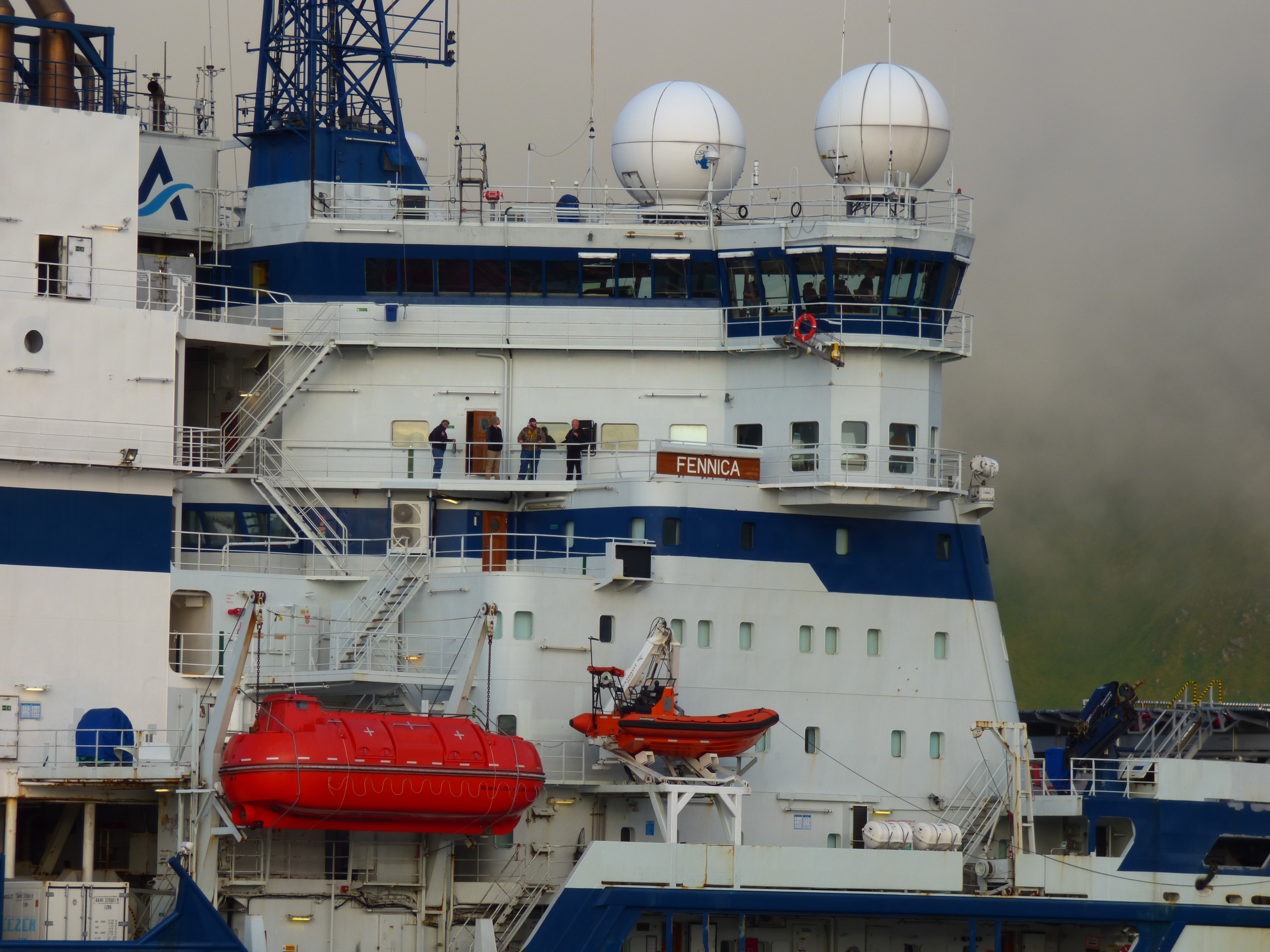

Shell Oil’s Fennica icebreaker departed Dutch Harbor, Alaska, for the Arctic Thursday afternoon, a day and a half after it arrived from Oregon.

The Fennica is now headed north on the 1,100-mile voyage to Shell’s Chukchi Sea drilling site.

The Fennica’s arrival in the Chukchi has been delayed by about a month after the icebreaker ran aground in Dutch Harbor on July 3. It then went through repairs and protests in Portland.

The Fennica has to be in place in the Chukchi before the U.S. Interior Department will let Shell drill into oil-bearing rocks beneath the sea floor.

Interior Department officials have told KUCB they expect to quickly approve the deeper drilling once the Fennica and its safety equipment are on site.

To Make A Science, You’ve Got To Break A Little Ice

Another icebreaker remains in Dutch Harbor: the Healy, the Coast Guard’s largest ship. It’s scheduled to depart on Sunday on its way to the North Pole.

The Healy is helping an international team of scientists study the rapidly changing chemistry of the Arctic Ocean. Many of the changes have been brought on by the burning of coal, oil and other fossil fuels around the world.

On Thursday afternoon, members of the scientific team were building a bubble of plastic sheets inside the Healy.

“The ship is kind of a dirty place,” geochemist Phoebe Lam from the University of California, Santa Cruz, said. “It’s rusty. There’s dust everywhere, and in order to do a lot of the measurements that we’re doing on this cruise, we need to create a clean environment.”

Inside the filtered air of that pressurized bubble, scientists will try to get uncontaminated measurements of dozens of different elements, compounds and isotopes, some of them common, some of them measured in parts per billion.

The Healy in Alaska's Dutch Harbor on Aug. 6. KUCB/John Ryan photo.

“A lot of the measurements we do are contamination prone,” Lam said. “Zinc is extremely contamination prone. You look at it, it gets contaminated. Everything has zinc coating…. It’s just everywhere.”

Lam’s focus is studying particles that drift slowly to the seafloor unless a current stirs them up.

“A biologist would call them plankton. A geochemist calls them particles,” Lam said. “It’s the same thing—it’s just stuff in the ocean.”

When asked if whales are just really big particles, she laughed.

“Yes. I hope not to get them because they’re hard to process.”

Lam said studying ocean chemistry is like doing forensics: It helps you understand what happened beneath the waves when you weren’t there to see it yourself. Scientists can use obscure elements and isotopes to address pressing questions like how fast the Arctic Ocean is taking up industrial greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere or why mercury is building up in the foods that Arctic peoples rely on.

Human Vs. Machine

Two robotic sail drones completed their first scientific mission in July, sailing 9,000 miles throughout the Bering Sea and taking millions of scientific measurements. Scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle hope to send the drones to the Arctic Ocean next summer.

“We can send these at very low risk and very low cost into some of harshest parts of the planet,” Saildrone Inc. CEO Richard Jenkins said.

But Dave Kadko of Florida International University, chief scientist on board the Healy, doesn’t think robots can replace humans any time soon, even if it costs a lot less to send a drone to the North Pole than an icebreaker full of researchers.

“They’re doing surface sampling, we’re sampling down to 3,000 meters. There’s a limit to what drones can do,” he said. “We’ll be embarking on the ice to measure ice, snow, melt ponds, the water underneath the ice, which drones can’t do.”

Avoid the Ice, Don’t Break It

This Arctic mission is the Healy’s second this year. Its first mission focused on testing equipment and practicing searches and rescues in polar conditions.

The Coast Guard only has two icebreakers in working condition, but it’s trying to expand its capabilities in the Arctic.

Captain Jason Hamilton, the Healy’s commanding officer, said the mission in July encountered more sea ice than expected, so the Healy detoured to the west.

“One of first rules of ice breaking is if you can avoid it, avoid it,” he said. “When you break ice, it’s more fuel. It is harder on the hull; it’s slower. So if you can take the path of least resistance, you take the path of least resistance.”

The upcoming mission has shifted to a more western route to avoid the icier parts of the Arctic. Scientists had intended to sail north toward the Pole along the 150th meridian—roughly the longitude of Anchorage and Prudhoe Bay.

“That’s heavily iced right now,” Kadko said. “Ironically, even though we’re in decades of diminished ice cover, this is a relatively heavier ice year.”

“Hopefully by time we get to Pole, the ice conditions at 150 will be improved,” he said.

On Wednesday, the National Snow and Ice Data Center reported that the overall area of Arctic sea ice for July was below the 30-year average but above the record low set in 2012. The center said the Northern sea route across the Arctic is now open.

Climate change has been shrinking the northern ice cap about 10 percent per decade. Polar shipping and mining are becoming feasible where they never were before.

The Healy is one of three icebreakers cruising the Arctic for science this summer. The international collaboration also includes scientists aboard Canadian and German icebreakers. They aim to get a baseline of conditions throughout the Arctic Ocean before the expected increase in shipping and resource extraction brings more pollution to the top of the world.