State Reveals Plans for Unalaska Children’s Services Office

Thursday, July 26 2012

For months, community leaders have been trying to get information about whether Unalaska’s child welfare office will reopen. Now, the Office of Children’s Services says it is working on a possible solution.

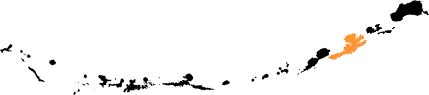

Technically, OCS has an office in Unalaska - there’s a sign on the door and a number in the local phone book - but the office has been empty since 2009. In 2010, the state stopped looking for someone to fill the vacancy. All reports of child abuse and neglect in the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands are sent to social workers in Homer and Wasilla.

Non-profit leaders and city officials in Unalaska aren’t happy with that arrangement, saying cases are slipping through the cracks.

“We need someone out here who can catch these situations before they get worse," says Lynn Crane, director of Unalaskans Against Sexual Assault and Family Violence. “The rest of us, we can offer services and try to help people access things that they need, but we can’t compel people to get what might be available to them.”

There’s also the issue of timeliness. Since 2008, OCS has responded to less than 25 percent of reported child abuse cases within the regulatory time frame. Eighteen percent were investigated more than 15 days late. When case managers do make it out, Crane says they don’t notify the relevant groups.

“I know that when they’re here their time is really precious and they get pulled in a lot of different directions, so I’m not trying to throw anyone under the bus, but that is one of the things we’d like to see improve. Improved coordination with local providers that maybe could try to fill in the gaps when they’re not here.”

Even better, Crane says, would be for OCS to reopen their field office in Unalaska. But OCS Director Christy Lawton says that’s not going to happen.

“I don’t think it would be appropriate, I don’t think it would be the best use of our resources, given the needs we have statewide.”

Lawton says the challenge of finding someone willing to live in the community, the cost versus the number of cases,and the difficulty of traveling from Unalaska to the Pribilofs all factor into that decision. But she says the state is working on an alternative. OCS has been in negotiations with the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association to provide child welfare services in the region.

“We have not ever engaged in this particular kind of partnership with tribes before, where they are acting on on our behalf, under our umbrella, under our same policies and procedures," Lawton says.

APIA already has a child services worker in Unalaska, but they only deal with cases involving tribal members. The new position would serve the entire community.

“There would basically be an OCS supervisor supervising the worker, that [sic] basically is doing the same job, would be held to the same policies and procedures, the same legal requirements," Lawton says.

Lawton isn’t expecting the arrangement to save the state any money, so I asked her why partnering with APIA is better than just funding a state position.

“To the degree that 60 percent of our kids at any time that are in OCS legal custody are Alaska Native, that is typically the driving force for how we approach who best to partner with.”

The agreement isn’t finalized yet -- there are some sticking points with the Department of Law, including how the state could represent APIA in court -- but Lawton hopes to have something in place by the fall.

If the proposed contract doesn’t work out though, it’s back to the drawing board. Lawton says she would still oppose having a full-time worker in Unalaska. The alternatives would be having someone in the community part-time or basing them out of Anchorage, as opposed to Homer or Wasilla.

Whatever happens, Lawton says she wants to involve the community in the discussion. She’ll be in Unalaska for APIA’s Regional Wellness and Governance Conference in September and she hopes concerned citizens will reach out to her with ideas, at the conference or beforehand.