Strange Orange Robots Sail Into Dutch Harbor. Just What Are They Up To?

Thursday, July 30 2015

Aquatic robots have been spotted in the Aleutian Islands. Two ocean-going drones were seen sailing into Dutch Harbor Monday night with no one on board. Just what are these orange robots doing out there--and should we be alarmed?

TRANSCRIPT

These robots are 18 feet tall. Each one has a bright orange wing of carbon fiber sticking up from a floating platform. At sea, they look like oversized windsurfers.

Using the wind for propulsion, and solar panels for their electronics, they’ve been traveling thousands of miles in the Bering Sea all by themselves.

It’s almost like they have minds of their own.

But these robots are working for good, not evil--we think.

Richard Jenkins is their creator. He’s the CEO of Saildrone, Inc., in California.

Jenkins: “They’re autonomous. You send them waypoints and a corridor, and they won’t venture out of the corridor regardless of wind or tides. They’re self-controlling. You just need a human to tell them roughly where to go.”

Hmm. Self-controlling. Not sure I like the sound of that.

Jenkins came up to Unalaska to take his robots out of the water and send them home after a three-month science mission.

Jenkins: “On the mast there, that little square thing pointing down? That is a laser, so it is an infrared camera, you could say. What it does, it tells you the sea surface temperature at the very top micron of the water.”

Great. Robots with lasers. What could possibly go wrong?

If these self-controlling machines haven’t gone rogue, they’ve been using their instruments to measure temperature, oxygen levels and 20 other conditions in the rapidly changing Bering Sea.

Scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the University of Alaska-Fairbanks and the University of Washington are collaborating on the high-tech project.

They say each drone can carry more than 200 pounds of scientific instruments. They can cruise the open ocean at up to 14 knots. They can boldly go where it would cost a lot more to send a ship full of human beings.

At a busy fishing dock on Unalaska’s Captain’s Bay, Jenkins says he launched the two sail drones from the very same dock in April.

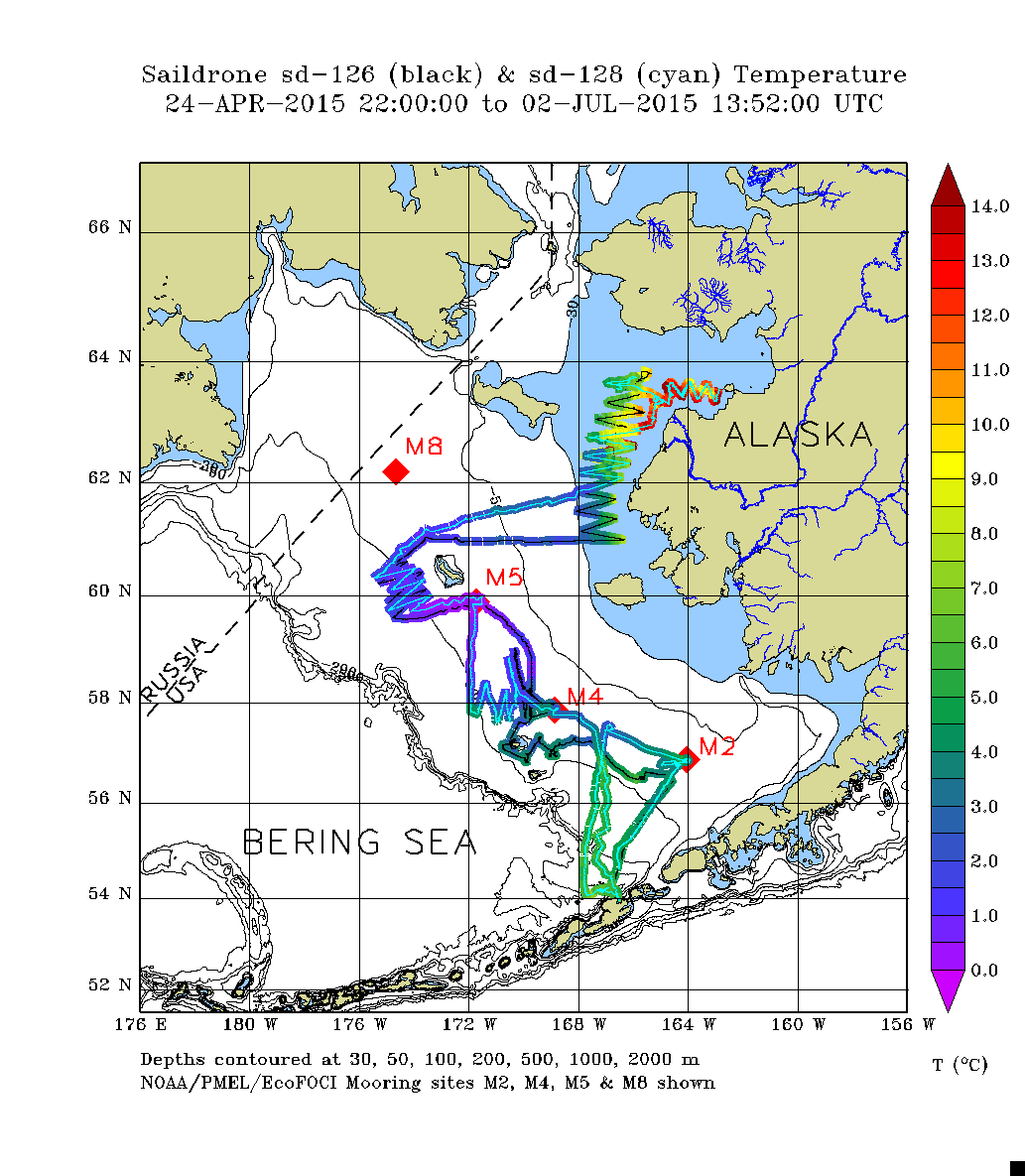

Jenkins: “We sent them out of here into 45-knot headwinds. From here, they went to St. Paul, then up through the Bering Sea up to Nome, then over to Norton Sound. We mapped the Yukon delta. Then they sailed back to Dutch Harbor. So 4,500 miles on each drone.”

Sea temperatures measured by two robots zigzagging across the Bering Sea. Courtesy NOAA/PMEL.

Jenkins says the last time humans surveyed the sea floor of the Yukon delta, the year was 1899.

Scientists hope new data from the drones can further human understanding of problems threatening Bering Sea fisheries. Problems like climate change and retreating sea ice. Problems that humans, not robots, have caused.

Ryan: “Who’s more intelligent, your drones or you?”

“[Laughs] Drones, for sure. No, Drones aren’t intelligent. Drones are robots that follow simple rules. They’re not able to make decisions for themselves. That’s all done back at base. You don’t want to have a whole heap of computer power on the drones because it’s a low power device. You only get so much energy from the sun, and computing power equals power consumption.

“This is just a pretty simple brain that actually just gets you from A to B and takes measurements.”

I guess that’s reassuring.

NOAA scientists say the drones’ biggest challenge isn’t subjugating the human race to their will, but dealing with cold water, limited sunlight and jellyfish.

Large numbers of jellyfish can clog the drones’ water intakes.

Isn’t that like War of the Worlds, where the attacking aliens were felled by bacteria?

Jenkins says his creations handled the jellyfish and algae and storms of the Bering Sea beautifully.

Jenkins: “If these vehicles can survive the Bering Sea, they can survive any place on Earth.”

Great. So if the drones do rise up against their masters, there’s no place to hide.

Next year, scientists hope to send the drones beyond the Bering Strait and into the Arctic Ocean. Here’s Dr. Strangedrone, I mean, Richard Jenkins again.

Jenkins: “The Arctic is one of the cutting edges of climate change now. So getting to the Arctic to measure how fast the ice is melting and what happens to the ocean when it does melt is huge. Normally, that would be very, very expensive. You would need a big icebreaker. It’s a long way to go and very remote, whereas we can send these at very low risk and very low cost into some of harshest parts of planet.”

But what it the drones get sick of being sent to the harshest parts of the planet?

2001 movie clip: “Open the pod bay doors, Hal.”

“I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t let you do that.”

Of course, that’s just science fiction.

2001 movie clip: “I know that you and Frank were going to disconnect me, and I’m afraid that’s something I cannot allow to happen.”

In science non-fiction, Jenkins disassembles his sail drones on the busy fishing dock. He straps them down into their shipping crates. They don’t seem to put up any resistance.

Maybe they are just useful tools for gathering important data about our rapidly changing oceans.

Maybe.

In Unalaska, I’m John Ryan.